Commissioning and Testing Best Practices

Proper commissioning makes or breaks high-altitude generator performance. Here’s what I always insist on:

Load Bank Testing at Site Conditions:

- Never accept factory test results alone

- Perform full-load testing at actual site altitude and temperature

- Run at 100% of derated capacity for minimum 2 hours

- Monitor:

- Power output and quality (voltage, frequency, waveform)

- Engine parameters (exhaust temperature, boost pressure, oil pressure)

- Cooling system performance (coolant temp, radiator airflow)

- Fuel consumption rates

I’ve caught issues during site commissioning that would have caused failures during actual outages: inadequate cooling, fuel system air leaks exacerbated by altitude, control system calibration problems.

Transient Load Testing:

- Don’t just test steady-state loads

- Simulate motor starting and step-load changes

- Verify voltage dip/recovery and frequency stability meet IEEE standards

- At altitude, generator regulation is more challenging—ensure controls are properly tuned

Ongoing Monitoring and Optimization

Implement SCADA or Remote Monitoring:

Modern genset control systems can provide real-time data:

- Power output trending

- Engine performance parameters

- Fuel consumption tracking

- Maintenance alerts

- Remote diagnostics

For remote high-altitude sites, this capability is invaluable. I can diagnose issues remotely and dispatch technicians with the right parts, minimizing downtime.

Data-Driven Maintenance:

Track performance over time:

- Power output trending: Declining output indicates engine wear or air system problems

- Exhaust temperature trending: Rising temps suggest combustion issues or cooling degradation

- Fuel consumption changes: Increased consumption flags efficiency losses

- Oil analysis results: Monitors wear, combustion byproducts, coolant contamination

This predictive approach prevents unexpected failures, especially critical at remote altitude sites where logistics are challenging.

Seasonal Adjustments

Altitude sites often experience dramatic seasonal temperature swings:

Winter Operations:

- Cold reduces air density further (good) but creates starting challenges (bad)

- Implement block heaters or jacket water heaters

- Upgrade to low-temperature diesel fuel formulations

- Ensure battery warming systems function

- Consider auxiliary starting air systems for very cold conditions

Summer Operations:

- High temperatures compound altitude derating

- Verify cooling system capacity at design temperature

- Consider temporary shade structures for outdoor installations

- Monitor coolant levels and condition more frequently

- Adjust load management if approaching thermal limits

Fuel Quality Management

Fuel quality is always important but becomes critical at altitude where combustion is already challenged:

Fuel Storage Considerations:

- Implement fuel polishing systems for long-term storage

- Test fuel quality quarterly (water, particulates, biological growth)

- Maintain adequate turnover (use and replace) to prevent degradation

- Consider fuel additives for cold weather and biological protection

Fuel System Maintenance:

- Change filters proactively (don’t wait for restriction alarms)

- Inspect injectors regularly—poor atomization is worse at altitude

- Bleed air from fuel system meticulously—air leaks are exacerbated by lower atmospheric pressure

When to Consider Upgrade or Replacement

Sometimes optimization isn’t enough. Consider replacement if:

- Consistent power shortfalls: You’re regularly shedding loads or running at >90% capacity

- Excessive maintenance costs: Old naturally-aspirated engines at altitude may cost more to maintain than replace

- Technology gap: Upgrading to modern turbocharged, electronically-controlled engines can dramatically improve altitude performance

- Reliability concerns: When a failure would be catastrophic, don’t nurse along marginal equipment

I worked with a mine in Bolivia that struggled with aging naturally-aspirated generators for years. When they finally replaced them with modern Cummins turbocharged units, power availability improved by 30% and maintenance costs dropped by 40%. The payback period was under 24 months.

Conclusion: Respect Physics, Plan Accordingly

Altitude affects diesel generator power output in ways that are dramatic, predictable, and non-negotiable. The fundamental physics—reduced air density means less oxygen for combustion—applies universally whether you’re installing a 20kW unit in Denver or a 2,000kW system in the Andes.

The key takeaways from 15+ years of high-altitude generator commissioning:

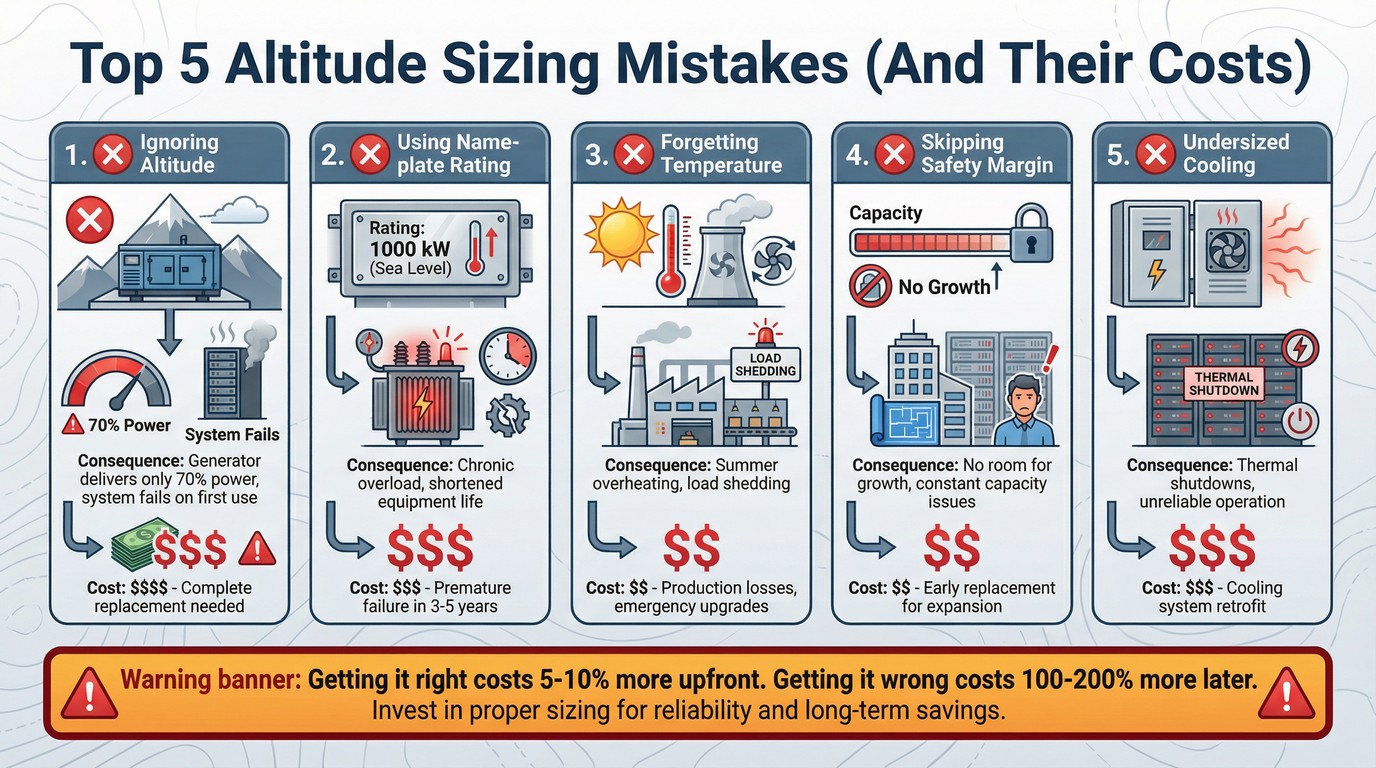

- Never specify generators based on nameplate ratings alone at altitude locations. Always apply proper altitude and temperature derating factors.

- Get manufacturer-specific derating data for your exact model. Generic rules-of-thumb are starting points, not substitutes for real engineering data.

- Turbocharged, aftercooled engines are worth the investment at high altitudes. The improved performance and reduced derating typically justify the higher upfront cost.

- Account for alternator derating separately from engine derating. The alternator can be the limiting factor in hot, high-altitude environments.

- Build in safety margins. A generator operating at 70-75% of its derated capacity will serve you reliably for decades. One sized exactly to its derated capacity will disappoint you.

- Commission and test at site conditions. Factory test reports don’t reveal how your generator will actually perform at 3,500 meters in summer heat.

- Partner with knowledgeable suppliers who understand altitude applications. Tesla Power and other experienced integrators can guide you through the specification process and ensure your complete generator package is optimized for altitude.

The cost of getting altitude derating wrong—undersized systems, production losses, retrofit expenses—far exceeds the cost of proper upfront engineering. Respect the physics, apply the data, build in margins, and your high-altitude generator performance will meet expectations.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How much power does a Cummins diesel generator lose at 5,000 feet altitude?

At 5,000 feet (approximately 1,524 meters), a Cummins diesel generator typically experiences a 12-18% power reduction compared to its sea-level rating, depending on whether it’s naturally aspirated or turbocharged. For example:

- Naturally aspirated engines: ~15-18% derating

- Turbocharged engines: ~12-15% derating

- Turbocharged + aftercooled: ~10-12% derating

So a 500kW rated generator at 5,000 feet will deliver approximately 410-440kW depending on the engine technology. Always consult the specific model’s derating table, as these figures vary by engine series. Temperature also plays a role—if the site experiences high ambient temperatures above 25°C (77°F), apply additional temperature derating on top of the altitude derating.

2. Can I install a sea-level rated generator at high altitude without modifications?

Technically yes, but you must understand that it will deliver significantly reduced power output. A “sea-level rated” generator doesn’t fail at altitude—it simply can’t produce its nameplate power due to the physics of reduced air density.

The critical requirement is proper sizing: calculate the derated capacity at your altitude and ensure it still exceeds your load requirements. For example, if you need 400kW at 3,000 meters, you might need to purchase a 600kW sea-level rated generator.

However, for high-altitude sites (above 2,000-2,500m), I strongly recommend specifying generators explicitly designed for altitude service, including:

- Turbocharged and aftercooled engines

- Oversized cooling systems

- Enhanced starting systems

- Control systems calibrated for altitude

These modifications improve reliability and longevity beyond just sizing up a standard unit.

3. Does altitude affect both prime and standby power ratings equally?

Yes, altitude derating applies equally to all duty classifications—ESP (Emergency Standby Power), PRP (Prime Rated Power), and COP (Continuous Operating Power). The derating percentage is based on the engine’s ability to ingest sufficient air mass, which is independent of duty cycle.

However, the practical impact differs:

- Standby/ESP applications: You only operate during outages, so you might accept tighter margins

- Prime/COP applications: You’re running continuously, so adequate derating margin is critical for longevity

For prime power at altitude, I recommend even more conservative sizing—targeting 70-75% utilization of derated capacity rather than 80-85%—because continuous high-load operation accelerates wear.

4. How does altitude affect diesel generator fuel consumption?

Altitude typically increases specific fuel consumption (fuel used per kWh produced) by 5-15%, even though the generator is producing less power. This seems counterintuitive but makes sense:

- Incomplete combustion: Less oxygen means fuel doesn’t burn as efficiently

- Lower thermal efficiency: The engine extracts less energy from each unit of fuel

- Increased engine effort: The engine works harder to produce the same output

For fuel storage and logistics planning at high-altitude sites, budget for:

- 10-15% higher fuel consumption per kW of actual output

- More frequent fuel deliveries if road access is limited seasonally

- Larger fuel storage to maintain adequate supply during winter road closures (common at mountain sites)

Proper fuel management becomes even more important at altitude, as fuel quality issues compound the combustion challenges already present.

5. What’s the highest altitude where diesel generators can realistically operate?

Diesel generators can operate at extreme altitudes, but with substantial power derating. I’ve personally commissioned installations above 4,500 meters (14,764 feet), and there are functioning systems even higher:

- Up to 3,000m (9,842 ft): Standard turbocharged generators with 20-30% derating

- 3,000-4,000m (9,842-13,123 ft): Purpose-built high-altitude packages with 30-40% derating

- 4,000-5,000m (13,123-16,404 ft): Specialized equipment with 40-50% derating; significant technical challenges

- Above 5,000m: Extremely rare; requires custom engineering and may not be cost-effective

At extreme altitudes, the practical limitation becomes economics rather than technical feasibility. When you need a 2,000kW nameplate generator to deliver 1,000kW of usable power, alternative solutions (grid connection, even if expensive; renewable + storage hybrids) may be more viable.

Other altitude-related challenges intensify at extreme elevations:

- Starting reliability decreases

- Cooling becomes critically challenging

- Maintenance is difficult due to remote locations

- Personnel may require altitude acclimatization

For sites above 4,000 meters, comprehensive engineering including site testing, customized packages, and extensive commissioning is essential.

References

- Cummins Power Generation – Generator Set Derating for Temperature and Altitude

- ISO 8528 Standards for Reciprocating Internal Combustion Engine Driven Alternating Current Generating Sets

- IEEE Standards for Emergency and Standby Power Systems

- Marathon Electric – Alternator Derating for Altitude and Temperature

- Tesla Power – Cummins Diesel Generator Sets

- NFPA 110 Standard for Emergency and Standby Power Systems

About the Author: This article draws on 15+ years of hands-on experience commissioning diesel generator systems at elevations from sea level to over 4,500 meters across North America, South America, and Asia. The technical guidance reflects current industry standards and manufacturer specifications as of 2025.

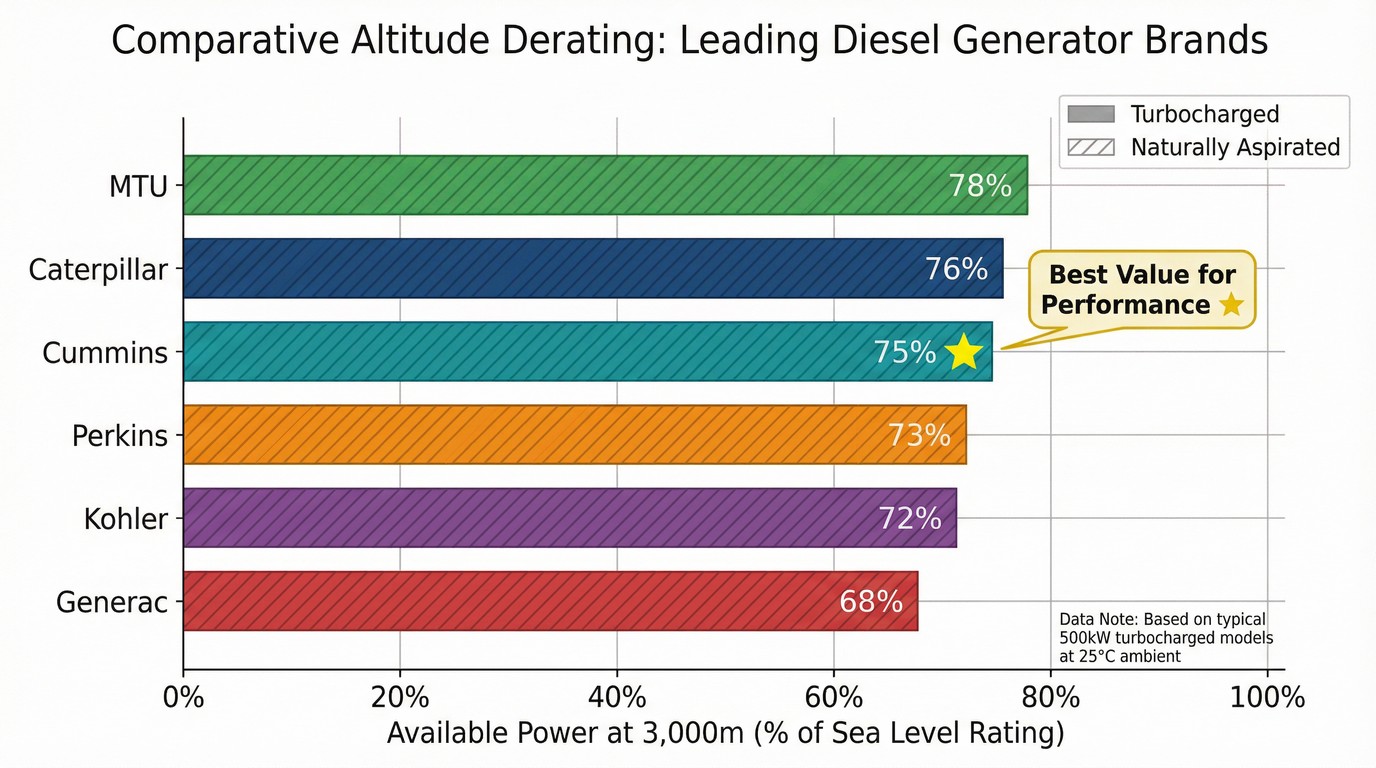

Figure 8: Comparative Brand Performance at 3,000m Altitude – While MTU and Caterpillar show slightly better altitude performance, Cummins offers the best balance of performance, derating predictability, and total cost of ownership for most industrial applications.

Tools and Methods for Proper Generator Sizing at Altitude

Manufacturer Derating Tables: Your Primary Resource

The single most important tool is the manufacturer’s own derating table for your specific generator model. Here’s how to use them:

Step 1: Obtain the correct datasheet

- Request the full technical datasheet, not just a product brochure

- Verify it includes altitude/temperature derating tables (often labeled “Table A” for Cummins)

- Confirm the data matches your exact model and engine series

Step 2: Identify your site conditions

- Altitude: Precise elevation in meters or feet

- Maximum ambient temperature: Worst-case summer conditions

- Barometric considerations: Add 150m (500ft) if site experiences persistent low pressure

Step 3: Apply the multiplier

- Locate the intersection of your altitude and temperature in the table

- Multiply the generator’s rating by this factor

- The result is your actual available power

Online Calculator Tools

Several manufacturers and third parties offer online generator sizing calculations tools:

Cummins Power Generation Sizing Tools:

- Available through Cummins distributors and the Cummins website

- Input load profile, altitude, temperature, duty cycle

- Provides recommended models with proper derating applied

Engineering Calculation Spreadsheets:

- Many consulting engineers maintain proprietary spreadsheets

- Incorporate manufacturer data with safety factors and load growth projections

- Can model complex scenarios like parallel operation and load shedding

Third-Party Sizing Software:

- Programs like PowerCalc, GenSize Pro

- Database of multiple manufacturer models

- Good for comparing brands and configurations

Load Analysis: Know What You’re Powering

Accurate generator sizing starts with thorough load analysis. Don’t just add up nameplate ratings—you need to understand:

Connected Load vs. Demand Load:

- Connected load = sum of all equipment ratings

- Demand load = actual simultaneous operating load (typically 60-80% of connected)

- Use demand load + safety margin for sizing

Motor Starting Current:

- Large motors draw 6-8× running current during startup

- This transient load can trip an otherwise adequate generator

- Calculate either:

- Largest motor starting + all other running loads, OR

- Use reduced-voltage starters / VFDs to reduce starting surge

Load Profile Over Time:

- Peak load vs. continuous load

- Daily and seasonal variations

- Growth projections (5-10 year outlook)

Safety Margins and Redundancy

Never size a generator to exactly match the calculated derated capacity. Build in margins:

<mark style=”background-color: #FFF3CD; padding: 2px 5px;”>Recommended sizing approach: (Maximum Demand Load × 1.25) / (1 – Derating Factor)</mark>

The 1.25 multiplier provides:

- 25% safety margin for load growth

- Accommodation for load calculation uncertainties

- Reduced stress on equipment (longer life)

- Better voltage/frequency regulation under varying loads

For critical applications (data centers, hospitals, emergency power systems), consider N+1 redundancy: install capacity for N generators required + 1 spare unit.

Professional Engineering Services

For installations over 500kW or critical applications, invest in professional power system engineering:

- Load study and power quality analysis: Identifies harmonics, motor starting issues, load diversity

- Single-line diagram development: Documents the complete electrical design

- Protection coordination: Ensures overcurrent devices operate correctly

- Altitude performance verification: May include computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis for cooling

The cost of professional engineering (typically 2-5% of project value) is cheap insurance against costly mistakes.

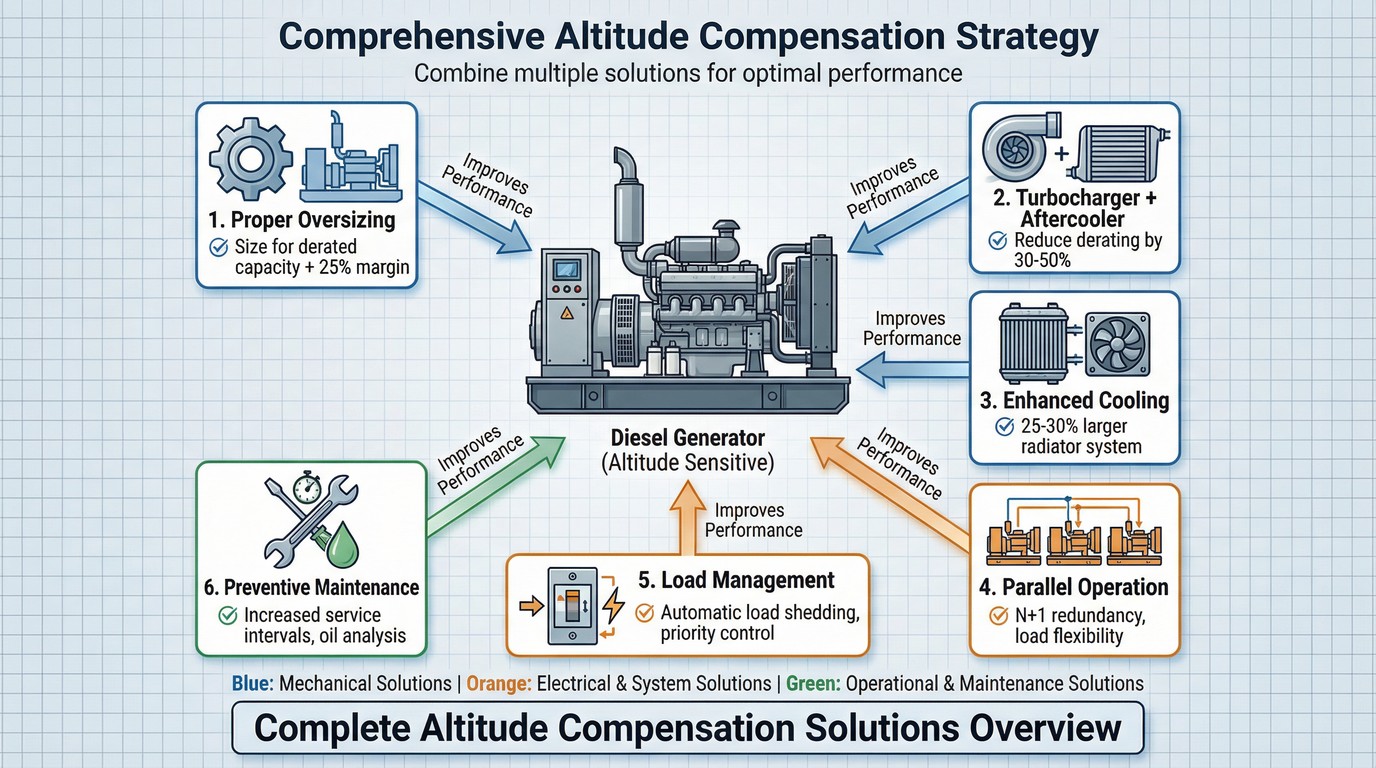

Figure 11: Comprehensive Altitude Compensation Strategy – Successful high-altitude generator installations typically combine multiple solutions: proper oversizing, turbocharged engines, enhanced cooling, parallel operation capabilities, intelligent load management, and optimized preventive maintenance programs.

Comparing Brands: Cummins vs. Competitors at Altitude

Why Brand Matters for High-Altitude Performance

Not all diesel engine derating factors are created equal. Different manufacturers take varying approaches to altitude compensation, and their published derating curves can differ significantly.

Cummins: The Benchmark

Cummins has extensive high-altitude experience, particularly in mining and oil & gas applications. Their strengths:

- Comprehensive derating data: Cummins publishes detailed altitude/temperature tables for virtually every generator model

- Wide turbocharged lineup: Most Cummins generator engines from 100kW up feature turbocharging as standard

- Field-proven reliability: Decades of operation in South American mines, Tibetan plateau installations, Rocky Mountain facilities

- Global support network: Critical for remote high-altitude sites

Typical Cummins derating: 3-5% per 1,000m for turbocharged models, with excellent temperature compensation data.

Caterpillar: Premium Performance

Caterpillar (Cat) generators are often considered the premium option, with comparable or slightly better altitude performance:

- ACERT technology: Cat’s advanced combustion systems optimize fuel delivery for varying conditions

- Aggressive turbocharging: Cat tends toward higher boost pressures, beneficial at altitude

- Integrated packages: Cat’s complete generator packages often include altitude-optimized cooling

- Higher cost: Typically 10-15% premium over comparable Cummins units

Cat’s derating curves are similar to Cummins—3-5% per 1,000m for turbocharged units—but some users report slightly better real-world performance at extreme altitudes (>4,000m).

Kohler: Value and Versatility

Kohler offers a broad range of industrial power systems with good altitude capabilities:

- KD-series: Kohler’s heavy-duty line performs well at altitude with proper derating

- Flexible configurations: Good options for parallel operation and load-sharing

- Competitive pricing: Generally 5-10% less expensive than Cummins equivalents

- Strong North American presence: Excellent for U.S. high-altitude installations (Rockies, Sierra Nevada)

Derating is typically in the 4-6% per 1,000m range, slightly more conservative than Cummins/Cat.

Generac: Residential to Light Commercial

Generac dominates the residential and light commercial market but has limited options for large industrial altitude applications:

- Good for moderate altitudes: Works well up to 2,000-2,500m

- Limited high-altitude engineering: Fewer purpose-built high-altitude packages

- Strong in smaller sizes: Excellent for 20-150kW applications

- Best value proposition: Most cost-effective for standby applications at moderate elevations

Perkins and MTU: Specialized Applications

Perkins (now part of Caterpillar) offers excellent smaller engines (20-600kW range) with good altitude characteristics, particularly popular in Europe and Asia.

MTU (Rolls-Royce Power Systems) represents the premium end for very large installations (500kW to 3,000kW+). MTU’s high-performance turbocharged engines handle altitude exceptionally well but command significant price premiums.

My Field Observations

After commissioning dozens of high-altitude installations, here’s what I’ve observed:

Best overall altitude performer: Caterpillar, but the cost premium is substantial.

Best value for performance: Cummins. Proven technology, extensive derating data, global support, competitive pricing.

Best for specific regions:

- North America: Kohler or Cummins

- South America: Cummins (dominant in Andean mining)

- Asia: Cummins or Perkins

- Premium applications: MTU or Caterpillar

<mark style=”background-color: #D1ECF1; padding: 2px 5px;”>For most industrial high-altitude applications, Cummins provides the best balance of performance, derating predictability, parts availability, and total cost of ownership.</mark>

The Role of Package Integrators

Remember, you’re not just buying an engine—you’re buying a complete generator package. Companies like Tesla Power integrate Cummins engines with alternators, control systems, and cooling packages optimized for your specific application. The quality of that integration significantly affects real-world altitude performance.

A well-integrated Cummins package from a knowledgeable supplier will outperform a premium engine poorly integrated by an inexperienced packager.

Figure 10: Common Altitude Sizing Mistakes and Their Costs – This infographic summarizes the five most frequent errors in high-altitude generator specification and their downstream financial impacts. Getting sizing right costs 5-10% more upfront but prevents 100-200% cost overruns from undersized systems.

Solutions and Compensation Strategies

Strategy 1: Proper Oversizing with Derating Calculations

The most straightforward solution is also the most reliable: specify a generator with sufficient nameplate capacity that, after altitude and temperature derating, still meets your actual load requirements.

The sizing formula:

<mark style=”background-color: #D1ECF1; padding: 2px 5px;”>Required Nameplate Rating = Actual Load Requirement / (1 – Derating Percentage)</mark>

For example, if you need 500kW at a site with 30% combined derating:

- Required rating = 500kW / (1 – 0.30) = 500kW / 0.70 = 714kW nameplate

So you’d specify an 800kW or 750kW generator to have proper margin.

This approach has several advantages:

- Predictable performance: You know exactly what you’re getting

- Standard equipment: No special modifications or custom engineering

- Better longevity: Operating at 70-80% of derated capacity gives excellent service life

- Future-proof: Built-in capacity for load growth

The disadvantage? Higher upfront capital cost. But in my experience, this is almost always the most cost-effective solution over the equipment lifecycle.

Strategy 2: Turbocharged and Aftercooled Engines

If you’re specifying new equipment for a high-altitude site, prioritize turbocharged diesel generators with aftercooling (also called intercooling).

How turbocharging helps:

A turbocharger uses exhaust gas energy to spin a compressor that forces more air into the engine cylinders. At altitude, where ambient air is thin, the turbo compensates by compressing that thin air to higher densities.

The beauty of exhaust-driven turbochargers at altitude: as elevation increases, the exhaust gas expands more aggressively through the turbine, actually helping the turbo spin faster. This partially offsets the reduced ambient air density.

Aftercooling adds another performance layer:

When you compress air, it heats up. Hot compressed air is less dense than cool compressed air. An aftercooler (intercooler) cools the compressed air from the turbo before it enters the cylinders, increasing density further and improving combustion efficiency.

Realistic performance:

Turbocharged + aftercooled diesel generators still require derating at altitude, but typically at much gentler rates:

- Naturally aspirated: 8-12% derating per 1,000m

- Turbocharged only: 5-7% per 1,000m

- Turbocharged + aftercooled: 3-5% per 1,000m

That difference is significant. At 3,000m elevation:

- Naturally aspirated: 24-36% derating

- Turbo + aftercooled: 9-15% derating

The improved altitude performance often justifies the higher initial cost of turbocharged equipment.

Strategy 3: Special High-Altitude Packages

Major manufacturers including Cummins offer specialized high-altitude generator packages. These typically include:

- Optimized turbocharger sizing: Larger or more efficient turbo units specifically selected for altitude

- Modified fuel mapping: ECU calibration adjusted for altitude air density

- Enhanced cooling systems: Oversized radiators and cooling fans

- Upgraded alternators: Alternators rated for high-altitude thermal conditions

- Starting system enhancements: Heavy-duty batteries and starting motors

These packages command premium pricing but deliver better performance than standard units at altitude.

Reputable suppliers like Tesla Power can provide Cummins-powered generator sets with proper altitude compensation engineering. When sourcing emergency power equipment for high-altitude installations, working with manufacturers who understand altitude derating is essential—they’ll handle the technical specifications and ensure the complete package (engine + alternator + cooling) is properly matched.

Strategy 4: Parallel Operation

For large load requirements at altitude, parallel operation of multiple smaller units can offer advantages:

Benefits:

- Better load matching: Run only the capacity you need at any moment

- Improved fuel efficiency: Partial-load efficiency is better with multiple units

- Built-in redundancy: N+1 or N+2 configuration provides backup capacity

- Modular expansion: Easier to add capacity as load grows

Considerations:

- Requires load-sharing controllers and synchronization equipment

- More complex electrical design

- Higher maintenance burden (multiple engines to service)

- Needs adequate space for multiple units

I’ve successfully implemented parallel configurations at mining sites where 3× 800kW generators provided better operational flexibility than a single 2,000kW+ unit.

Strategy 5: Load Management and Shedding

Sometimes the most economical solution isn’t larger generators—it’s smarter load management.

Implement intelligent load shedding:

- Priority classification: Identify critical vs. non-critical loads

- Automatic transfer: Install contactors that automatically shed non-critical loads if generator capacity is reached

- Demand management: Stagger large motor starts; prevent simultaneous starting of multiple large loads

- Load monitoring: Real-time monitoring with alerts before overload conditions

This approach works particularly well for standby power systems where the generator only operates during grid outages. You might be able to live without HVAC chillers or certain production equipment during emergency operations, allowing a smaller (less expensive) generator to handle truly critical loads.

Strategy 6: Preventive Maintenance Optimization

Operating at altitude increases stress on generators. Compensate with more aggressive maintenance:

Air filter service:

- More frequent filter changes (dust at altitude sites, especially mining, accelerates filter loading)

- Consider pre-filters or upgraded filter media

- Monitor intake restriction carefully

Fuel system attention:

- Fuel quality is critical—poor fuel compounds altitude combustion problems

- More frequent fuel filter changes

- Consider fuel polishing systems for stored fuel

Cooling system:

- Check coolant strength and condition more frequently

- Clean radiator fins regularly (critical at altitude where cooling margin is reduced)

- Monitor coolant temperatures closely

Oil analysis:

- Institute regular oil sampling and analysis

- Incomplete combustion at altitude can lead to fuel dilution of oil

- Watch for elevated wear metals indicating combustion issues

What Doesn’t Work (Lessons from Failures)

Let me save you from mistakes I’ve witnessed:

❌ “We’ll just run it derated”: Buying a 500kW generator for a 500kW load and “planning to run it at 70% because of altitude” means you’re actually running it at 100% of available capacity. That’s a recipe for shortened life and potential failures.

❌ Ignoring alternator limits: Specifying an engine upgrade without verifying alternator thermal capacity. I’ve seen projects where they upgraded to a more powerful engine but kept the same alternator—the alternator became the limiting factor.

❌ Relying on manual load shedding: “We’ll just turn things off if we need to.” In the middle of a winter storm at 3 AM, will your operators correctly and quickly shed the right loads? Automate it.

❌ Skimping on cooling: “The engine is producing less power, so it doesn’t need as much cooling.” Wrong. The cooling challenge is often WORSE at altitude. Don’t downsize cooling systems.

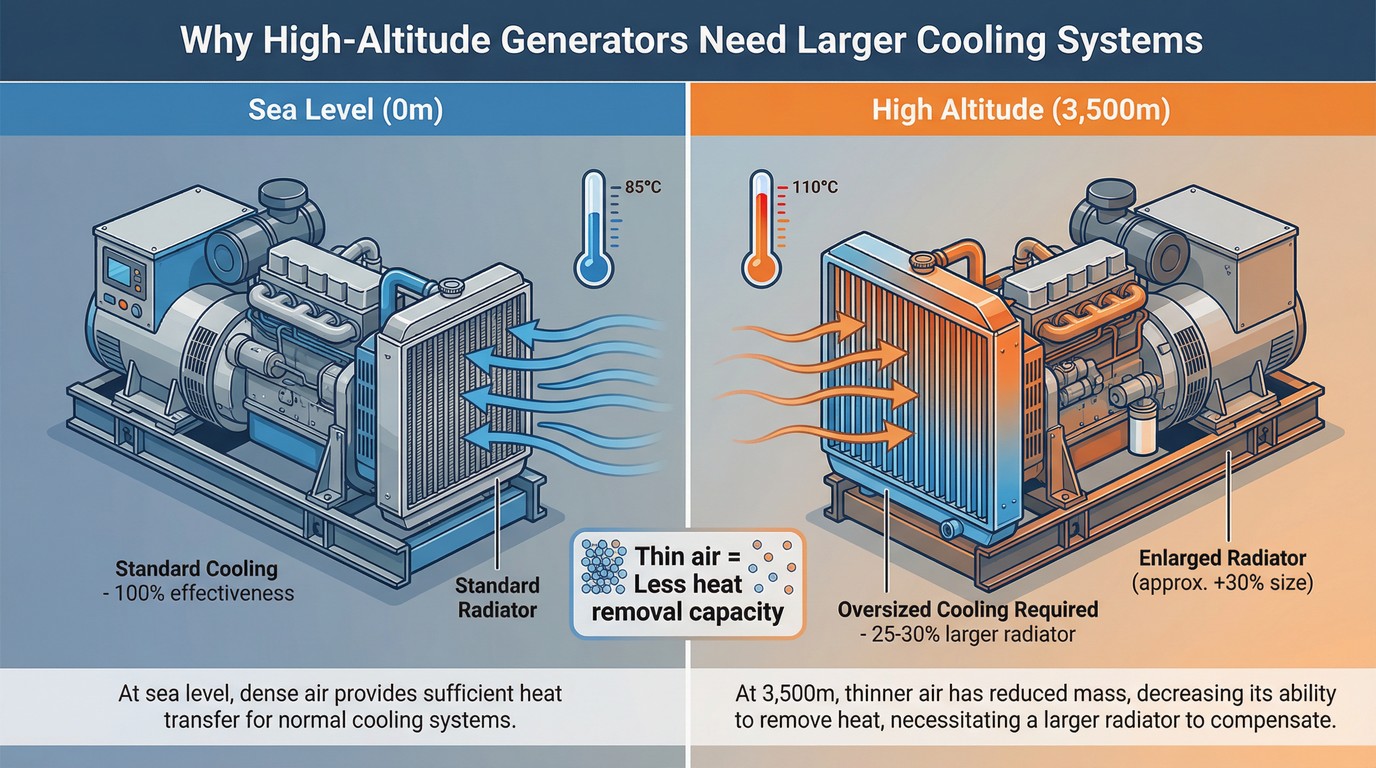

Figure 7: Cooling System Requirements at Altitude – High-altitude generators require 25-30% larger radiators because thin air has reduced heat removal capacity. This counterintuitive requirement often surprises engineers who assume lower power output means less cooling need.

Fuel Consumption Changes

Diesel fuel consumption at altitude doesn’t scale linearly with power. In fact, you’ll often see HIGHER specific fuel consumption (fuel per kWh produced) at altitude because:

- Combustion efficiency decreases

- The engine works harder to produce the same output

- Incomplete combustion wastes fuel energy

Budget for 10-15% higher fuel consumption per kW of output when planning fuel storage and logistics for high-altitude sites.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

I want to emphasize the downstream costs of undersizing:

- Immediate operational failure: Generator trips on overload during first serious power outage

- Frequent load shedding: You’re constantly deciding which loads to shed, disrupting operations

- Shortened equipment life: Running a generator at 95-100% capacity continuously dramatically reduces engine life

- Retrofit costs: Replacing an undersized generator is FAR more expensive than specifying correctly initially

- Lost production: For prime power applications and continuous duty generators, every hour of load-shedding is lost revenue

The Peru mining project I mentioned earlier? They eventually had to buy a second, larger generator and operate both in parallel—essentially doubling their capital cost and significantly complicating their electrical system. All because altitude derating wasn’t properly accounted for during initial specification.

Figure 6: Generator Control Panel Display – Modern Cummins generator control systems display real-time power output, load percentage, and active altitude derating factors, enabling operators to monitor performance against derated capacity.

Real-World Impact: What This Means for Your Installation

Common Installation Scenarios

Let me walk you through some typical scenarios I’ve encountered, because this is where altitude derating moves from spreadsheet calculations to actual operational consequences.

Scenario 1: Hospital in Denver, Colorado (1,600m / 5,280 ft)

A hospital specifies a 500kW standby generator for their critical care facilities. Denver’s “Mile High” elevation requires modest but real derating.

- Altitude effect: ~16-18% power reduction

- Available power: Approximately 410-420kW

- Impact: Still adequate for the planned 380kW critical load, but safety margin is tighter than expected

The lesson: Even “moderate” altitudes eat into your safety margins. If you’re sizing for N+1 redundancy or future expansion, altitude derating becomes critical in your planning.

Scenario 2: Data Center in Quito, Ecuador (2,850m / 9,350 ft)

Data centers have zero tolerance for power interruptions. A facility specifies Tier III redundancy with multiple 1,000kW Cummins generators.

- Altitude effect: ~28-30% power reduction

- Available power per unit: Approximately 700-720kW

- Impact: The N+1 redundancy that looked comfortable on paper barely covers the actual load during single-unit outage

The client had to upsize their entire generator fleet, adding 30% to their capital expenditure. This is exactly why early-stage altitude analysis saves money.

Scenario 3: Mining Operation in Tibet (4,500m / 14,764 ft)

This is extreme altitude territory. A processing plant needs reliable prime power for 24/7 operation because grid power is unavailable.

- Altitude effect: ~40-45% power reduction

- Additional temperature effect: Summer temps at 30°C add another 3-5%

- Combined available power: Only 50-55% of nameplate rating

<mark style=”background-color: #FFCCCC; padding: 2px 5px;”>At extreme altitudes, you’re essentially buying a generator rated at double your actual power need. A 2,000kW generator delivers roughly 1,000-1,100kW usable power.</mark>

The cost implications are massive, but there’s no way around physics. The alternative—undersized power—means constant load-shedding, equipment damage, and production losses.

Beyond Power: Other Altitude Effects You Need to Know

Starting Performance

Cold-starting a diesel engine is harder at altitude. The combination of lower air density and reduced battery performance in cold mountain environments means:

- Longer cranking times: The engine needs more revolutions to build sufficient compression heat

- Battery capacity issues: Cold reduces battery capacity; altitude increases starting load

- Fuel system challenges: Diesel fuel atomization is less effective with reduced air density

I always recommend upgrading to heavy-duty starting batteries and ensuring block heaters or jacket water heaters for high-altitude installations, especially in cold climates.

Cooling System Challenges

Here’s an interesting paradox: your engine is producing less power at altitude, but it’s actually HARDER to cool. Why?

- Lower air density means each cubic meter of cooling air carries less heat capacity

- Radiator effectiveness drops because there’s less air mass flowing through the fins

- Higher exhaust temperatures from incomplete combustion add to the thermal load

Many high-altitude installations require oversized radiators—sometimes 25-30% larger than sea-level specifications. When I’m reviewing generator packages for altitude sites, I always verify the radiator sizing explicitly.

Introduction: When Your New Generator Delivers Only 70% Power

I’ll never forget the phone call I got from a mining operations manager in Peru three years ago. They’d just installed a brand-new Cummins 500kW diesel generator at their facility—about 4,200 meters above sea level in the Andes. The generator was supposed to handle their entire processing plant. But when they fired it up and loaded it, they couldn’t get more than 350kW out of it.

“Is the generator defective?” he asked me, frustration clear in his voice.

The generator wasn’t defective. It was doing exactly what physics demanded at that elevation. And that’s the harsh reality many facility managers discover too late: altitude dramatically affects diesel generator power output, and if you don’t account for it during the specification phase, you’ll end up with an undersized system.

In this article, I’m sharing what I’ve learned from 15+ years of commissioning Cummins diesel generators at elevations ranging from sea level to over 4,500 meters. We’ll dig into the engineering principles behind altitude derating, walk through actual calculation methods, and explore the solutions that actually work in the field. Whether you’re specifying a standby power system for a mountain resort, a prime power application for a high-altitude data center, or backup power solutions for industrial facilities, understanding altitude effects isn’t optional—it’s essential.

Why Altitude Matters: The Physics Behind Power Loss

What Actually Happens to Air at High Altitude

Let me start with the fundamental issue: air density. At sea level, standard atmospheric pressure is about 1013 millibars (or 101.3 kPa). The air is packed with oxygen molecules—about 21% by volume—that your diesel engine needs for combustion.

As you climb in elevation, atmospheric pressure drops. And here’s the critical point: the air doesn’t just get “thinner” in some abstract sense. The actual mass of oxygen per cubic meter decreases. At 1,000 meters (3,280 feet), you’ve lost about 10% of your air density. At 2,000 meters, it’s roughly 20% less. By the time you hit 4,000 meters—where some mining operations and mountain facilities operate—you’re working with nearly 40% less air density than at sea level.

Your diesel engine doesn’t care about volume; it cares about mass. Each intake stroke pulls in the same volume of air, but at altitude, that volume contains significantly fewer oxygen molecules. Less oxygen means less complete combustion, which directly translates to less power.

The Combustion Efficiency Problem

Diesel engines rely on a very specific air-to-fuel ratio for optimal combustion. In a naturally aspirated engine (one without forced induction), you’re entirely dependent on atmospheric pressure to fill the cylinders.

Here’s what happens at altitude:

- Reduced oxygen availability: With 10-40% less oxygen depending on elevation, the fuel can’t burn as completely

- Lower combustion temperatures: Incomplete combustion means lower peak temperatures in the cylinder

- Decreased thermal efficiency: The engine extracts less mechanical energy from each unit of fuel

- Increased exhaust temperatures: Unburned fuel and incomplete combustion products exit at higher temperatures

- Higher emissions: Incomplete combustion produces more carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, and particulates

Temperature Compounds the Problem

Altitude isn’t the only factor. Ambient temperature plays a huge role too, and this is where things get particularly challenging for high-altitude installations.

Air density depends on both pressure AND temperature. Hot air is less dense than cold air. So if you’re installing a diesel generator at 3,000 meters in a desert environment where summer temperatures hit 40°C (104°F) or higher, you’re facing a double penalty:

<mark style=”background-color: #FFF3CD; padding: 2px 5px;”>Combined derating: Lower atmospheric pressure (altitude) + higher air temperature = even greater power loss</mark>

I’ve seen installations where the combined altitude-temperature derating reduced available power by 30-35% compared to the nameplate rating. That’s the difference between a generator that can handle your load and one that trips offline during peak demand.

Why Diesel Engines Are Particularly Sensitive

Diesel engines are compression-ignition engines. Unlike gasoline engines that use spark plugs, diesels rely on compressing air to extremely high pressures (and temperatures) to ignite the fuel. This process is inherently dependent on having sufficient air mass in the cylinder.

When you start with less air mass due to altitude, several things happen:

- Compression ratio effects: You’re compressing less mass, which means less heat generation during compression

- Fuel atomization issues: Proper diesel combustion requires fine fuel droplets mixing with hot compressed air

- Turbocharger performance changes: Even turbocharged engines face challenges, as the turbo is working with lower-density exhaust gases

This is why turbocharged diesel generators handle altitude better than naturally aspirated ones—but even they require derating, which we’ll cover in the solutions section.

Understanding Cummins Derating Factors and Calculations

How Cummins Rates Their Generators

Before we dive into derating, you need to understand how Cummins power output is specified in the first place. Cummins, like all major manufacturers, rates their generators according to ISO 8528 standards, with engine reference conditions defined by ISO 3046.

The baseline ratings you see in spec sheets assume:

- Air inlet temperature: 25°C (77°F)

- Atmospheric pressure: ~1013 millibars (sea level)

- Relative humidity: 30%

Those are ideal conditions. Your actual installation site? Probably not so ideal.

Cummins provides ratings in several duty classifications:

- ESP (Emergency Standby Power): Maximum power available for emergency use, variable load, limited hours per year

- PRP (Prime Rated Power): Continuous power with variable load, unlimited running hours

- COP (Continuous Operating Power): Constant load, continuous operation

All of these ratings are stated at the reference conditions above. When your site differs—and it almost always does—you must apply derating.

The Derating Methodology

Cummins publishes derating tables (often called “Table A” in their technical documentation) that provide multipliers based on altitude and temperature combinations. The process is straightforward:

<mark style=”background-color: #FFF3CD; padding: 2px 5px;”>Derated Power = Catalog Rating × Derating Multiplier</mark>

Here’s where it gets interesting: Cummins actually recommends adding 150 meters (500 feet) to your site altitude when you’re in an area with persistently low barometric pressure. This accounts for weather-related pressure variations that go beyond simple geometric elevation.

Typical Derating Values for Cummins Generators

While specific derating factors vary by model and engine series, here are some representative examples I’ve pulled from actual Cummins datasheets:

For Cummins DF-Series engines:

- Up to 1,000m (3,280 ft) @ 40°C: No derating required

- 1,000m to 2,000m: Derate by 2.4% per 305m (1,000 ft) above 1,000m

- Above 2,000m: Additional 6.4% per 305m (1,000 ft)

- Temperature: Additional 4.2% derating per 11°C above 40°C

For Cummins QSK23-G1 series:

- Altitude derating: 5.0% per 300m (1,000 ft)

- Temperature derating: 7.0% per 10°C above reference

Let me work through a real example because this is where theory meets field reality.

Example Calculation: Mining Site at 3,500 Meters

Let’s say you’re specifying a Cummins diesel generator for a processing facility at 3,500 meters (11,483 feet) in the Andes. Summer ambient temperatures reach 35°C.

Starting point: Cummins C550 D5e generator, 550kW ESP rating at sea level/25°C

Step 1 – Altitude derating:

Using the conservative rule (approximately 4% per 1,000 feet above 3,000 feet for this elevation range):

- Elevation above baseline: 11,483 – 3,280 = 8,203 feet

- Approximate altitude derating: 8,203 ft × 0.04 per 1,000 ft ≈ 33% reduction

Step 2 – Temperature adjustment:

- Ambient is 35°C vs. 25°C reference = +10°C

- Temperature derating: ≈3-4% additional

Combined effect:

- Total derating: ~35-37%

- Actual available power: 550kW × 0.65 ≈ 358kW

<mark style=”background-color: #FFCCCC; padding: 2px 5px;”>Critical reality check: That 550kW generator can reliably deliver only about 360kW at your site conditions. If your load requires 500kW, you’re significantly undersized.</mark>

This is exactly what happened with that Peru mining project I mentioned earlier. They specified based on nameplate ratings without proper altitude compensation.

Model-Specific Considerations

Here’s something that trips up even experienced engineers: derating factors are NOT universal across all Cummins models. A turbocharged, aftercooled engine will have different derating characteristics than a naturally aspirated engine of similar displacement.

For example:

- Naturally aspirated engines: More aggressive derating, typically 8-12% per 1,000m

- Turbocharged engines: Better altitude performance, typically 3-5% per 1,000m above certain thresholds

- Turbocharged + aftercooled: Best altitude performance, but still requires derating

When I’m specifying industrial generator systems for altitude, I always request the specific model’s derating table from Cummins or the generator package manufacturer. Don’t rely on generic rules of thumb—get the actual data for YOUR specific engine series.

Generator vs. Engine Derating

One more critical point: the alternator (generator end) also requires derating at altitude and high temperature, separate from the engine derating.

The alternator produces heat that must be dissipated through cooling air. At altitude, that cooling air is less dense and less effective at removing heat. Most alternator manufacturers specify maximum ambient temperatures (typically 40°C at sea level) and require additional derating above that or at altitude.

So your final available power is the LOWER of:

- Engine derated power

- Alternator derated capacity

I’ve encountered situations where the alternator thermal limits were actually more restrictive than the engine limits, particularly in hot, high-altitude environments.